The Field Beyond the Hedge

A Tale of Expectation and Contentment

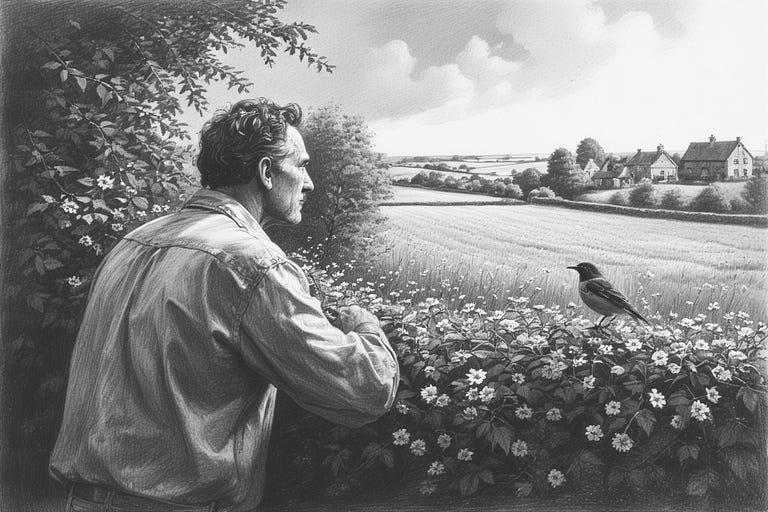

The sun had not yet climbed above the hedgerows of Appletree Farm when Thomas Paxton stepped into the dew-laced grass, his boots sinking softly into the emerald carpet. The birds, always first to greet the day, piped their ancient chorus, and the mist lay in bands across the fields as if the earth itself had drawn a blanket against the chill. Appletree was an old farm in the heart of North Yorkshire, its lands passed down through generations like secrets, its rhythms as constant as the rising sun.

Thomas, now in his fortieth year, bore the weight of these rhythms with a kind of stoic affection – a farmer’s love, neither sentimental nor blind, but rooted and enduring. His father had taught him that the land was both gift and challenge, and as he watched the vapour wreathe the wheat, Thomas found himself pondering the age-old question: Do we expect too much of life, or not enough of the right things?

The Expectation of Plenty

In the small village that clustered around Appletree’s fringe, expectation was a subtle but powerful force. It manifested in the market on Saturdays, when neighbours compared products and whispered hopes for rain or sun. It lived in the eyes of Thomas’s children, Sarah and Jack, as they scampered across the orchard, dreaming of adventures beyond the farm. It coloured the letters his wife, Margaret, wrote to her sister in London, lines filled with longing for city lights and bustle.

For Thomas, expectation had always been tied to the land. Each spring, he sowed seed and hoped for a bountiful yield; each autumn, he measured the harvest against years past. There were years of plenty, when the wheat stood tall, golden with promise, and there were lean years, when the rain fell too hard or the frost came early, flattening hope like a scythe. Through them all, Thomas had learned to temper his dreams, to ask not for abundance but for enough – a modest crop, a healthy family, a roof unbowed by storm.

Yet as the world beyond Appletree grew louder – machines in place of men, supermarkets swallowing local shops, the internet promising worlds at the click of a mouse – Thomas wondered if something essential was being lost. Was it possible that life, for all its modern miracles, was slipping past people unnoticed, like the mist that vanished with the dawn?

The Field Beyond

On a brisk September morning, Thomas received a letter. It was from a cousin in Hull, inviting him to see a new farming innovation: drones for sowing and reaping, computer-driven soil analysis, and crops engineered for perfection. The cousin wrote with excitement, describing endless possibilities and profits. “The future is here, Tom,” he concluded. “Why settle for less?”

Thomas folded the letter and placed it on the kitchen table. Over tea, Margaret asked what he thought. “Do you ever wish for more?” she said, not looking up as she stirred her cup.

Thomas considered. “I suppose I wish for some things,” he replied, “but I wonder if wishing for more is just wishing for different troubles.”

He walked out to the fields that afternoon, the letter in his pocket, his mind heavy. The wheat rustled in the wind, and overhead, a kestrel hovered, watching for a meal. As Thomas paced the boundary of his land, he looked across the hedge to a neighbouring field, untended and wild, thistles nodding in the breeze. It struck him then: perhaps expectation was not about wanting more, but about wanting rightly.

The Right Things

That evening, Thomas sat by the fire with Margaret and the children. The wind outside rattled the windows, but inside, the room glowed with lamplight and laughter. Jack was reading aloud from a book of farming tales, and Sarah was drawing pictures of lambs in her notebook. Thomas watched them, feeling a warmth that was both pride and gratitude.

He thought of the cousin’s letter again. The promise of efficiency, of unending growth, of fields engineered to yield more than nature ever intended. Yet here, in the simple act of being together, Thomas saw a different kind of abundance – one that could not be measured in bushels or profit.

“Dad,” Sarah piped up, “will the farm always be ours?”

Thomas smiled. “If we care for it, and each other, I hope so.”

He realised, as the fire crackled, that much of life’s disappointment comes not from asking too little, but from asking for the wrong things: perpetual success, unending excitement, certainty in a world made of change. The farm had taught him that seasons shift, crops fail, and joy is often found in the resilience to begin again.

Harvest Home

As autumn deepened, Thomas worked the fields with renewed purpose. He tended the hedges, repaired the stone wall by the pond, and helped Jack build a birdhouse for the robins. Margaret and Sarah pressed apples in the old barn, their laughter echoing among the rafters. The days shortened, and the evenings were cool, but there was a richness to them, a feeling that enough was, indeed, enough.

In October, the village gathered for the Harvest Festival. Appletree’s wheat was not the tallest nor the most plentiful, but Thomas brought a sheaf to the church with quiet pride. The vicar spoke of gratitude, of finding blessings in small things – a warm hearth, a loyal friend, a field that yields just enough.

Later, as the moon rose above the farm, Thomas stood at the gate and looked out over the land. He saw the patchwork of fields, the orchard’s shadow, the old barn with its mossy roof. He felt the expectancy of tomorrow, but not as a burden, rather, as an invitation.

The Measure of Enough

The next morning, Thomas rose with the sun. The mist curled along the valley, silver and soft. He walked the familiar path through the fields, his boots damp with dew, and felt the pulse of life around him – steady, generous, and real.

Perhaps, he thought, people often expect too much of life in the wrong ways: they chase bigger harvests, brighter futures, grander stories. But the right things – the closeness of family, the cycles of nature, the quiet satisfaction of tending a small corner of the world – these are never too much to hope for.

As he reached the field beyond the hedge, Thomas paused. The wildflowers nodded, the robins sang, and the farm, in all its imperfection, was enough. And in that enough, he found everything.